- Home

- Matthew Ollerton

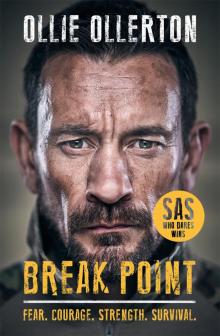

Break Point

Break Point Read online

BREAK POINT

BREAK POINT

OLLIVE OLLERTON

Published by Blink Publishing

The Plaza,

535 Kings Road,

Chelsea Harbour,

London, SW10 0SZ

www.blinkpublishing.co.uk

facebook.com/blinkpublishing

twitter.com/blinkpublishing

Hardback – 9781788702065

Trade Paperback – 9781788702072

Ebook – 9781788702089

All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or circulated in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing of the publisher.

A CIP catalogue of this book is available from the British Library.

Copyright © by Matthew Ollerton, 2019

Matthew Ollerton has asserted his moral right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them.

Blink Publishing is an imprint of the Bonnier Books UK

www.bonnierbooks.co.uk

This book is dedicated to my mum, whose unconditional love and care held firm even when all around her was falling apart.

To my amazing girlfriend Laura, who will never quite understand just how much she helps me grow.

And to my son Luke, who I missed every day and never forgot.

Names, locations, procedures and specific events

have been redacted to protect the security of those

involved and the practices of the British Special Forces.

Everything else has been described as it happened.

CONTENTS

Prologue

1Maverick Marine

2Wild Child

3Losing Battle

4Shotgun Willy

5So Near, So Far

6Mummy’s Boy

7The Widest Smile

8Special, At Last

9Rather Beautiful

10Square Peg, Round Hole

11Over and Out

12Peace in War

13The Road to Baghdad

14Tempting Death

15One Last Job

16False Dawn

17Happy Now?

18Who Dares Wins

19Just Like You

20Iron Ladies

21The Business

22In Control

Epilogue

Pictures

Acknowledgements

PROLOGUE

There was not much to see on the road from Amman to Baghdad. There was sun, of course, searing a mighty hole through acre after acre of blue. Camels and goats, foraging for unseen greenery. The odd bomb crater and chewed-up vehicle, including a bright red Ferrari, which would have made more sense on the moon. And mile after mile of highway, hugged by a watery haze and cutting a swathe through the flat and featureless desert landscape.

We’d been on the road for what seemed like forever when it was my turn to take the wheel. I’d travelled 14 hours the day before and was driving on autopilot, my mind and body merged with the vehicle and tarmac beneath it. Before I’d set off that day, I’d been convinced – hopeful, even – that something big might break the monotony. But as the milometer ticked over, all I could think about was getting home and collapsing in my pit.

It was as I was telling my colleague Dave of my evening’s plans that something caught my eye in my wing mirror. I looked over my shoulder to see headlights flashing behind us. It was about 17:45 and there were no other vehicles on the road. My immediate thought was that it was the American military. No problem. But as the vehicle gathered speed and drew closer, I realised that it couldn’t be the Americans, because the vehicle – a black Mercedes – had blacked-out windows. I then thought it might be a security company. But if it was, what did they want me to do? Pull over? There was no way I was taking that risk.

I informed Dave that we had a possible target to the rear. Dave informed me that there were in fact two pursuing vehicles. As I was considering the possibilities, the windows came down on the front vehicle and four AK47s emerged. Oh, fuck. I glanced to my left and saw a sign that said ‘FALLUJAH’, and it dawned on me: that something big that I thought might happen – that I’d desperately wanted to happen – was happening, in the very place I’d imagined. ‘Talk about tempting fate,’ I thought to myself. ‘You fucking idiot…’

My body began to roast from the toes upwards. My senses heightened, which happens when you are suddenly pitched into blackness. My mind contracted into a tangled ball of confusion so that I couldn’t think. I’d gone into shock. It was as if I’d died for a second and was looking down on myself. I had no idea what I was going to do. I felt very alone, vulnerable and pathetic. An image flashed through my mind: me on the side of the road, minus my head. But it wasn’t just me who was in danger of being killed, I was responsible for Dave behind me and 12 civilians piled into vans in front, employees of ABC News.

The pressure and anxiety were about to spill over when gunfire rang out. AK47 fire is very distinct and very intimidating. When there are four going off at the same time, it’s like some hellish orchestra, extremely noisy and extremely nasty. In fact, and rather appropriately, it sounds like the cracking that signals the start of an avalanche. But when a couple of rounds came over the top of our vehicle, which might have buried some people, it was as if a hypnotist had clicked his fingers, bringing me out of my trance. In the military, as soon as it gets noisy, it gets real. It was at that moment that my training kicked in.

I knew that unless I tamed the stress, we were all going to die. So I gained control of my breathing, stripped away all the shit that didn’t matter, and began to think rationally. The people in the vehicles in front didn’t matter, it was my actions that mattered, because it was my actions that would affect them. I had to put aside all the different pressures and anxieties and deal with the threat. That was the only way to resolve the issue at hand.

It had all happened so fast, but once I had my breathing under control, everything slowed down. In effect, I was able to control the speed of events. Some might think a second is simply a second, end of story. But a second is only as short or long as the person who experiences it. You can decide how long a second is, but only if you’re at ease with the situation you’re in. If you’re stressed and panicking, a second will feel like no time at all. If you’re not, it can feel two or three times as long. You only have to watch sport to realise this. Most people facing a punch thrown by a professional boxer would wear it and hit the deck. But another professional boxer might see that punch coming, slip it and come back with one of his own. That’s what I had to do.

I gave Dave the order to stand by and flung our vehicle towards the middle lane to our right. It wasn’t a move I thought about, it was just instinct. The enemy pulled up beside us on our left, which was quite foolish of them: they were now boxed in by the central reservation and had no idea who we were or whether we had weapons. As it happened, I had my left hand on the steering wheel and my right hand on my MP5 kurz, which was on my lap. Meanwhile, Dave was sitting behind me with an AK47 of his own.

I checked the safety catch on my weapon was off and looked to my left through the closed window. I’d been in gunfights before, but this was the first time I’d seen the whites of the enemy’s eyes. I was no more than two feet away from the guy in the passenger seat. I could have reached out and touched him. He was just a boy, wearing an Arab headdress and white robes. ‘This kid is the same as me,’ I thought, ‘ju

st working for someone else.’ His expression wasn’t aggressive or menacing, he looked like he didn’t want to be there.

As uncomfortable as the boy looked, he still did what he thought he had to do. His AK47 fell in line with my head, as did the AK47 behind him. I stared even more intently into the boy’s piercing blue eyes, as if trying to make a telepathic connection. I desperately wanted to hear him say, ‘Don’t worry, I’m not going to shoot you.’ Instead, silence. I really didn’t want to do what I needed to do. But all he had to do was feather the trigger and that would have been it. I had to take action. I was at break point. If I took the situation to the next level – poked the hornets’ nest – it might make things worse. But it was my only hope to make things better. If I did nothing, we were going to get shot and people might die. Including me.

Stacked up against the door, balaclavas on, weapons at the ready. Who exactly is behind that door is anyone’s guess. There is nothing but silence. But when we go in, it might get very noisy very quickly. People might get shot. People might go down. People might end up dead.

Contrary to what some people believe, Special Forces soldiers aren’t supermen. We’re just ordinary people. We can’t see through walls or round corners. Bullets don’t bounce off us and we don’t hit the target with every shot. But, because no plan survives first contact, what we do is train and plan meticulously, so that we’re battle-ready. If the shit hits the fan, we’re ready to rock. Or at least we should be.

In computing, a ‘break point’ is defined as ‘an intentional stopping or pausing place in a program, put in for debugging purposes’. In the Special Forces, we’re so highly trained that we know when a break point is approaching and that we need to pause and ‘debug’. That’s when we take a couple of deep breaths to lower the cortisol levels, which in turn gives us greater focus. We call that recalibration. Then we do our thing. In fact, that’s a Special Forces mantra: Breathe. Recalibrate. Deliver. It’s our way of regaining control of a situation that might be spiralling off in a dangerous direction.

But break points aren’t exclusive to soldiers in the Special Forces, they’re in all of us. Our lives are dictated by break points, every day is full of them. They don’t have to happen in dramatic circumstances, while you’re dressed head to toe in black, wielding a laser-sighted machine gun and climbing up the side of a ship. A break point might be a crisis that needs solving in the office, an unexpected bill that needs paying or a relationship that’s taken a turn for the worse. It can be even more mundane than that. A break point might be a sink full of dishes and having to decide whether to wash them before you go to bed, so that you’re not faced with a kitchen full of clutter in the morning and are ready to go again. A break point might be spending the evening working on your business plan, instead of getting shitfaced down the pub. Break points are about going the extra mile, clambering over obstacles – even while travelling in what seems like the wrong direction – and facing down negatives to achieve your ambitions.

A break point is a moment you decide nothing will stand between you and your goal; a moment you decide to step out of your comfort zone in order to move forward and grow as a person; a moment you refuse to accept your self-imposed limits and go beyond what you thought you were capable of. As such, break points are more mental than physical. It might seem strange to describe coming under attack in Fallujah as being in one’s comfort zone. But more comfortable than trying to fight our attackers off would have been accepting my fate and waiting to die. I knew I had to make a decision that might make our attackers even more dangerous than they already were. But it was the only way I was going to escape the situation.

Some people think that being comfortable is a good thing, but that isn’t necessarily the case. Someone might feel comfortable working in an office Monday to Friday; taking home a comfortable wage; living in a comfortable house; driving a comfortable car; going on comfortable holidays twice a year. But comfort isn’t normally conducive to growth and contentment. Despite your comfortable existence, you might be dying inside.

The problem is that the alternative can seem terrifying. Like making the decision to hit your attackers before they hit you. It usually means rejecting your comfortable existence and voluntarily entering a scary world of uncertainty; a world that is, on the face of it, worse than the one you’re already in. But by daring to step out of your comfort zone, you might be creating opportunities to make life better.

1

MAVERICK MARINE

Being told you can’t do something can be incredibly empowering, often even more so than having everything laid out for you on a plate. So I should probably thank my old maths teacher for being so negative. I was 14 at the time, chatting away in class as usual, and the teacher – not for the first time – let me have it: ‘Ollerton! Pay attention!’

I sprung to my feet, like a Jack released from a box.

‘I don’t give a fuck about this! I’m joining the Marines!’

The teacher sneered at me from behind his desk. ‘Ollerton, you’ll never be in the Marines. You’ve got no discipline.’

That was a turning point. Almost an epiphany. It was the moment I realised that school and academia wasn’t for me. And never would be. The teachers all said that I was intelligent, but I had no interest in studying. I had no interest in being part of an out-of-date system that was all about churning out little glove puppets for society: people who worked behind desks in offices, people who had expensive weddings, big mortgages and lots of debt.

The education system didn’t suit me, like it doesn’t suit a lot of people. I didn’t want to be programmed like the other kids, have all the creativity and dreams drummed out of me. That was something I wasn’t willing to accept. I was a rebel. I couldn’t be doing with people telling me to do things I didn’t want to do.

People who don’t conform are treated with suspicion. If you’re not interested in what they put in front of you at school, you’re written off as a nuisance and you end up ignored and ostracised. Society isn’t concerned with how well you perform as an individual, it’s concerned with how well you fit into the system. But I’ve always believed that if you want to fulfil your potential, don’t conform.

My maths teacher thought that because I refused to conform at school, it would be impossible for me to conform in the military. He thought that because I didn’t have the discipline for school-work, I didn’t have the discipline for soldiering. What he failed to see was that I simply wasn’t interested or stimulated by what he was trying to teach me.

While teachers and schoolmates thought I was losing it, in fact it was around that time that I started to find my way. True, I was flunking exams and bunking off school, phoning up and pretending to be my mum in a ridiculous high-pitched voice: ‘Matthew is ill today and won’t be coming in…’ (It never occurred to me to try to impersonate my dad instead, although my voice was probably closer to my mum’s anyway.) But I had woken up. I wasn’t a lost cause at all. For all my troubles, I was in a privileged position. I was that rare kid who knew exactly what he wanted to do with his life. There was no point flogging a dead horse, because I could already visualise where I wanted to be in a few years’ time. All I cared about was becoming a soldier. I was there in spirit. I could already see myself dressed in green with a gun over my shoulder.

That wasn’t the only time that someone in authority wrote me off as a kid. I can vividly remember going to the Royal Navy Marines careers office with my mum and saying I wanted to join. The woman behind the desk replied, ‘If you get into the Royal Marines, what do you want to do?’

I’d studied the brochure in detail. I knew every word and every picture. So immediately after she said that, I flipped to the middle pages, where there was a photo of a combat swimmer inside a submersible insertion craft. I pointed to it and said, ‘That’s what I want to do.’

The careers officer looked at me and laughed. ‘Everyone wants to do that. What do you really want to do?’

‘That’s

what I really want to do.’

‘Fine. Well, good luck with that…’

She could have said, ‘Wow, what a great ambition. If you work hard, you’ll do it.’ Instead, she laughed in my face. That’s the military for you, every bit as suspicious of non-conformists as the education system.

But it’s probably the best thing she could have done. It’s not as if I walked out of that meeting thinking, ‘I’ll fucking show you.’ But a seed had been sown in my subconscious. That photo of the combat swimmer in his submersible insertion craft was a symbol of what I might be able to achieve if I refused to accept the limits imposed on me by others.

I loved my country and the idea of being part of a tight-knit family – a brotherhood. Since the age of 14, I’d been living it every day. Everything I watched and everything I read was to do with the military. I’d flick through Combat Survival magazine and daydream about being in battle and fighting an enemy. Getting in seemed inevitable. Had I not, it would have killed me.

My grandfather had been a captain in the Royal Engineers and I’d been captivated by the Falklands War as a kid, especially the TV images of soldiers returning as conquering heroes, to the sound of cheers and the sight of a thousand Union Jacks being waved. That was the last of the proper land wars, and the last Britain fought alone. When you’re a boy, you only see the glamour and manliness of war, which is what gives you the passion to want to join up. You’re not privy to the bits in between, the horrific realities that lead to broken minds and bodies and hundreds of shattered lives all over the country.

Someone else who unwittingly motivated me to join the military was a guy called John. He was from my home town and there was a lot of friction between us, in part because I got off with his girlfriend. It was him who made me investigate joining the Royal Marines, because he’d become this bigwig around town since joining up himself. Whenever he came back from training, he and his mates would turn up at the appropriately named Clowns nightclub and there would be a big shout out from the DJ: ‘Welcome home to John, our resident Royal Marine!’ I’d be leaning against the bar thinking, ‘What a cock.’ But I was more jealous than anything.

Break Point

Break Point